Anthem for Doomed Youth

StoriesBenjamin Britten was born in 1913, into a time before the First World War, but he will have had no memory of that era. Young people of his age grew up in the shadow of the war, perpetually aware of the slaughter: recalling the generation that had been throw into the meat-grinder of the Western Front, determined that this should never happen again.

For the young people who grew up in the 1920s and 1930s, the poets of the First World War raised powerful voices against violence, and Wilfred Owen, who died in the final week of the war, spoke perhaps loudest of all. When Britten came to write his great testament against violence, the War Requiem, it was for the consecration of a new cathedral in Coventry, replacing the one destroyed by the Luftwaffe in 1940, but it was to Wilfred Owen’s poetry from the previous war that he turned. Owen gave him the clarity and intensity that the work required.

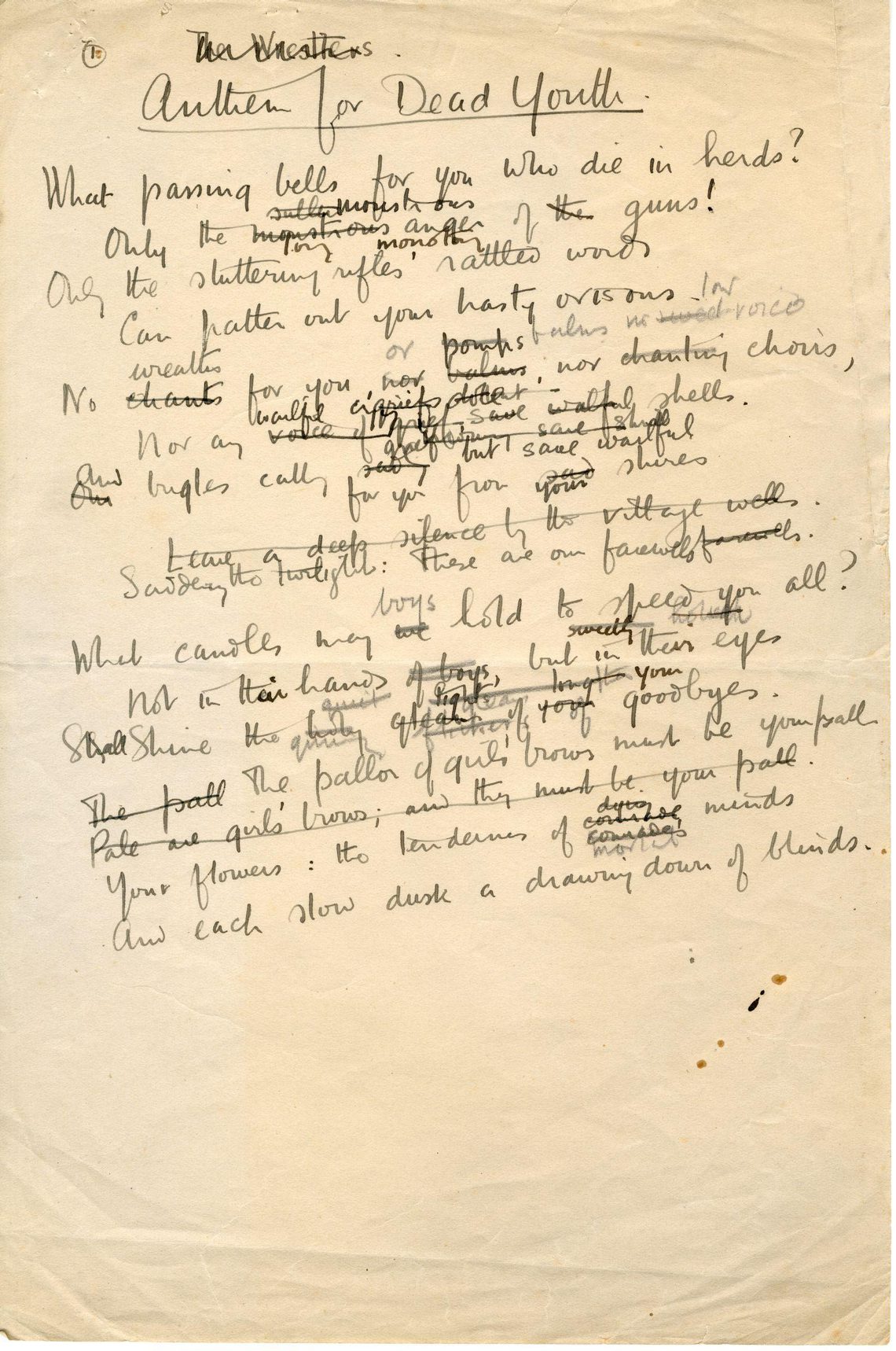

The War Requiem was premiered in 1962. The following year, Wilfred Owen’s brother Harold wrote to Britten to thank him for including Wilfred’s poetry in the work: Owen was not, then, as well known as he is now, and there was a tendency to read his work as social history rather than on its own merits. Harold sent Britten a gift that now has a proud place in the Red House archive: one of Wilfred’s working drafts for his “Anthem for Doomed Youth”, maybe his best-known poem and one sung in the Requiem.

In it, we see the poet casting about for the right words to bring his ideas to life. A sonnet, the poem has fourteen lines, and Owen already knows the endpoint: the final line, “And each slow dusk a drawing down of blinds,” is exactly as it would be in the finished version, but his route to that point is still uncertain. The first line would change: here we have “What passing bells for you who die in herds?” where the final, stronger version reads “…for these who die as cattle”: the finished version is more concrete. Also, of course, the third line has to rhyme with the first, so the version we hold at the Red House speaks of “the stuttering rifles’ rapid words”, where the finished version as “the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle”: again, we see why Owen made the change, adding the onomatopoeia that makes the line sound like the gunfire it describes.

The Red House archive allows us to sit in on Britten’s creative process and here we get to see Owen’s too, looking over his shoulder as he puts the poem together: sending a message from the Western Front to a post-war world he would never see.