The 2024 open season at The Red House brings two new exhibitions, one centring on the Aldeburgh Festival founded by Britten and Pears, and one on the two men’s art collection.

In the Exhibition Gallery, “The Composer’s Place” looks back over the history of the Aldeburgh Festival, how it was rooted in its location, and how this exemplifies Britten’s relationship to place. From its foundation in 1948 the Festival has balanced two seemingly opposed elements, being local and intimate in its scale yet bringing international arts of the highest quality to this small town: proudly rooted and local, but never provincial.

Twin displays expand on each of these themes, illustrated by reproductions from the rich sources in the Archive. Photographs and documents tell the story of Britten’s links to his native county and the influence its landscape had upon him. On the facing wall we see material reflecting the Festival’s role in bringing international talents to the Suffolk coast, in which Yehudi Menuhin and Mstislav Rostropovich rub shoulders with the Indian dancer Indrani Rahman.

Britten’s Church Parable Curlew River, premiered sixty years ago as part of the 1964 Festival, encapsulates this balance. Its roots are international, and lie in Britten and Pears’ lives as a globe-trotting performing duo. On tour in Japan in the 1950s, they witnessed a performance of ancient traditional Nō theatre, an art-form deeply rooted in Japan’s culture and its past. Curlew River, the fruit of ten years’ thought about that experience, is Britten’s answer to how this very specifically Japanese form might be given a European analogue. His solution was to root his piece in the forms and spaces of the Christian church, which for most members of a European audience would form a cultural background as deep-seated and recognisable as the conventions of Nō would be to Japanese watchers. Here, Britten’s rootedness in England and specifically his local Suffolk landscape - Curlew River was premiered in Orford church – serves not to limit him, but to unlock a route into a radically-different culture, to make possible an act of imaginative empathy that crosses cultural boundaries.

Image gallery

A gallery slider

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears at the piano with Aaron Copland; c.1949

Credit : Photographer unidentified

Peter Pears at a gathering of the Asian Music Circle featuring the dancer Indrani Rahman, in the Jubilee Hall, Aldeburgh; early 1960s

Credit : Photographer unidentified

Benjamin Britten, Peter Pearse and Yehudi Menuhin; c.1957

Credit : Photographer unidentified

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears with the Tokyo Madrigal Society in Japan; 16th February 1956

Credit : Photographer unidentified

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears with friends and hostesses at a Geisha evening in Kyoto, Japan; February 1956

Credit : Photographer unidentified

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears eating ice creams with members of the cast of 'The Rape of Lucretia' during an English Opera Group tour; August 1947

Credit : Photographer unidentified

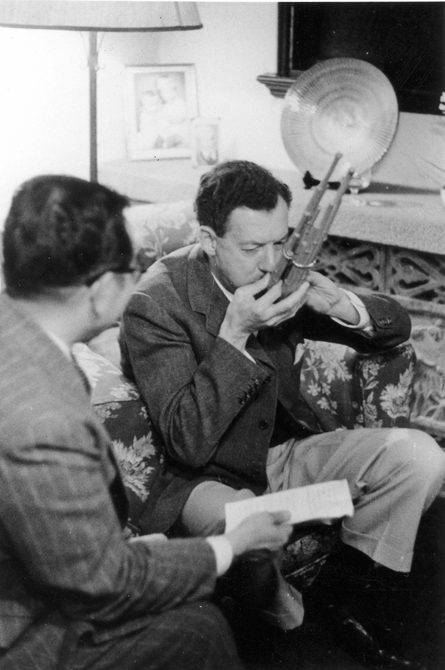

Benjamin Britten playing the shō, a Japanese wind instrument; February 1956

Credit : Photographer unidentified

Benjamin Britten and Imogen Holst at an Aldeburgh Music Club night at Crag House, Aldeburgh; 1954

Credit : Photographer unidentifiedBritten’s Church Parable Curlew River, premiered sixty years ago as part of the 1964 Festival, encapsulates this balance. Its roots are international, and lie in Britten and Pears’ lives as a globe-trotting performing duo. On tour in Japan in the 1950s, they witnessed a performance of ancient traditional Nō theatre, an art-form deeply rooted in Japan’s culture and its past. Curlew River, the fruit of ten years’ thought about that experience, is Britten’s answer to how this very specifically Japanese form might be given a European analogue. His solution was to root his piece in the forms and spaces of the Christian church, which for most members of a European audience would form a cultural background as deep-seated and recognisable as the conventions of Nō would be to Japanese watchers. Here, Britten’s rootedness in England and specifically his local Suffolk landscape - Curlew River was premiered in Orford church – serves not to limit him, but to unlock a route into a radically-different culture, to make possible an act of imaginative empathy that crosses cultural boundaries.

Britten’s composition draft for Curlew River forms a centrepiece of the exhibition. This is one of the manuscripts that, after Britten’s death, were presented to the nation by his executors in lieu of death duties. It is now the property of the British Library, although housed here in the Red House Archive on indefinite loan, and as such has a special status in the archive, housed under conditions of particular security and not normally brought out for display. This is a rare opportunity to see Britten’s workings for this important piece, and we are grateful to the British Library for allowing us to display the manuscript.

Reproductions of all seventy-five Festival programme book covers form a time-line along the final wall of the exhibition. Along the sequence, particular events are picked out, to give a flavour of the exhibition over the years. There are the great works of the Western canon, challenging new pieces, music from other traditions, discussions of literature and displays of the visual arts, and activities reflecting the Festival’s location in the very specific Suffolk landscape: this mixture is key to the Festival’s distinctive flavour, and has been since 1948. Selecting the events to highlight involved agonising choices, and for each one chosen, three or four had to be discarded. Only near the very end of the line does the richness pause, briefly, where two blank grey rectangles represent the ghosts of the 2020 and 2021 Festivals, the years in which COVID-19 led to the first ever cancelled programmes; it is good to see the bright colours resume after this interruption, with the covers for 2023 and for this year.

Across the courtyard in the ground floor of the Red House is this year’s exhibition drawn from the two men’s art collection, “Pears and Colour”. Pears was the dominant figure in assembling the collection: while Britten, living and breathing music, was the ears of the partnership, Pears provided the eyes. His collecting was bold and personal, focussing chiefly on twentieth-century art. It was never driven by an orthodox art-historical narrative, a sense of which “significant” artists “ought” to be included, but instead by his own likes. Some of these were personal – many of the artists were friends of the two men – but above all the driver was whether or not Pears liked the work, the simple factor of whether he wanted to have this piece on their walls. Our selection this year, similarly, abandons intellectual themes and looks at the works purely in visual terms, focussing on works with a bold sense of colour. (Sir Kenneth Clark lectured at the 1963 Aldeburgh Festival on “The Liberation of Colour”, speaking about how “[in] modern painting… colour has taken the place of form as the general means of expression”: we follow in his footsteps.) The selection includes British artists such as John Craxton, Philip Sutton or Robert Colquhoun, and European figures such as Christian Rohlfs, Joseph Scharl and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska: what unites them all is a vibrant sense of colour, one that will make the Red House gallery space glow.

We hope that these two exhibitions provide a thought-provoking introduction to this year’s 2024 season at the Red House: we look forward to welcoming you.

More to explore...

Volunteering at The Red House, Aldeburgh

Have you ever wondered what happens behind the scenes at The Red House when it’s closed for the winter season? We spoke to two of our…

Exhibition

Pears and Colour

A group exhibition featuring pieces from the Britten Pears Arts Collection, exploring a joyful thread in Peter Pears' collecting interests: primary colour.

28 Mar – 03 Nov 2024

More info

Exhibition

The Composer’s Place: Britten, the Festival and his Suffolk Home

An exhibition exploring Britten and Pears’ lives in Aldeburgh and how this coastal town inspired them to establish the Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts.

28 Mar – 03 Nov 2024

More info