We are celebrating the ‘B’ list of composers featured in this year’s Festival.

Watch our introductory video, and find out more about the fascinating connections between some of the Bs below.

Britten and Bridge

Britten came from a family of Bs: his siblings were named (or nicknamed) Bobby, Beth and Barbara. His mother, even when Britten was a child, had ambitions for him to become the fourth composing B after Bach, Beethoven and Brahms. But the most important musical B in his early years was Bridge whom he met at the age of 13. They were an unconventional match. Britten was a shy and slightly awkward adolescent, possessing a fierce determination to be a composer from a very young age.

Bridge, 34 years older, was a garrulous, expansive, somewhat bohemian figure given to tearing around the Sussex countryside at great speed in his car. Yet they instantly bonded and Bridge became Britten’s mentor, teaching him not only about composing but about how to live as a musician. When Britten left for the USA In 1939, Bridge presented him with his own viola and a note urging Britten to “just go on expanding”. They never met again (Bridge died in 1941) but Britten remained grateful to his teacher for the rest of his life.

Benjamin Britten

Britten at the Festival

15 June Suite on English Folk Tunes and Nocturne

22 June Songs and Proverbs of William Blake

22 June Our Hunting Fathers

24 June Three Divertimenti

26 June Opera arias and arrangements

26 June A.M.D.G.

27 June Winter Words and Folk songs

27 June Four Sea Interludes

28 June Seven Sonnets of Michelangelo

28 June Sea Interludes (film installation)

29 June Music for Brass

Bridge at the Festival

14 June Three Idylls

Brahms at the Festival

22 June Lieder

- Britten and Beethoven (and Bach and Brahms): In a diary entry on 13 November 1928 (aged almost 15) Britten wrote, “Brahms has gone up one place in my list of Composers. Beethoven is still first, and I think always will be. Bach or Brahms comes next, I don’t know which!” He later revised downwards his views of both Brahms and Beethoven, but Bach remained a favourite.

- Britten and Berkeley (and Berkeley): Britten and Lennox Berkeley collaborated on an orchestral suite called Mont Juic in 1936. It is based on a series of Catalan dances and was written after the two composers attended a music festival in Barcelona. Britten was later godfather to Berkeley’s son, composer Michael Berkeley.

- Britten and Bernstein: Bernstein conducted the first American performance of Britten’s opera Peter Grimes at Tanglewood, Massachusetts in 1946. The two got on reasonably well, though Britten apparently once punched Bernstein in the chest to get him to stop talking.

Boulez and Berlioz

Boulez has been described as “classical music's maverick”. As a composer he was an innovator, and a believer in radical change. The son of an industrialist, his father wanted him to become an engineer. He didn’t, and went to the Paris Conservatoire instead. A century or so earlier Berlioz was classical music’s “wild child”, given to obsessive passions and convention-busting symphonies. The son of a doctor, his father wanted him to become a medic. He didn’t, and went to the Paris Conservatoire instead.

The music of these two composers is wildly different: Boulez, while abandoning engineering, nonetheless appreciated the mathematical and systematic in music. Berlioz was extravagantly emotional, creating fantastical sounds for the orchestra and devising elaborate fantasy worlds. Yet in his other career as a conductor, Boulez was a fan of Berlioz’s revolutionary style, perhaps recognising something of himself. In 1967 he recorded a series of Boulez’s orchestral works – a fitting tribute from one maverick to another.

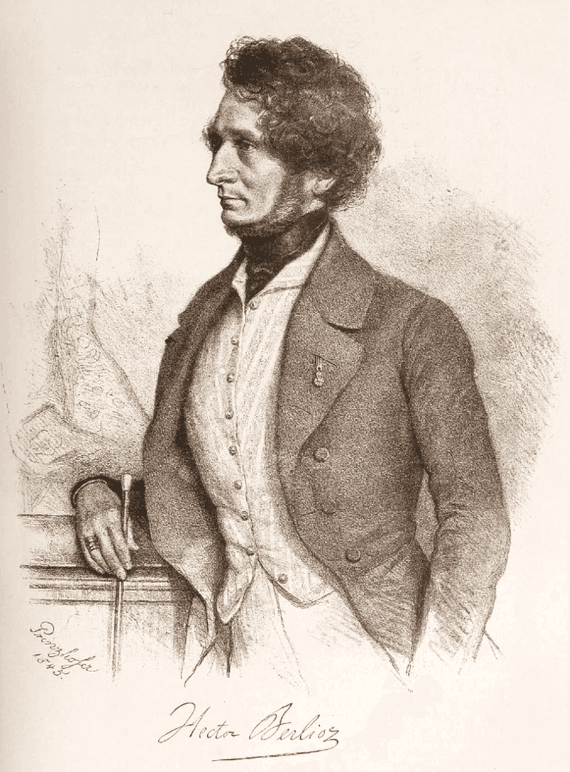

Hector Berlioz

Boulez at the Festival

19 June Film: Tele-marteau

20 June Dialogue de l’ombre double

23 June Le Marteau sans maître

29 June Mémoriale

Berlioz at the Festival

29 June Le corsaire and Symphonie fantastique

Berio at the Festival

20 June Sequenza I and Ricorrenze

21 June Surrounded by Sequenzas

- Boulez and Berio: these two giants of twentieth century music share a year of birth (1925), making 2025 their joint centenary year. Boulez dedicated his piece for clarinet and electriconics Dialogue d’ombre double to Berio for his sixtieth birthday in 1985.

- Boulez and Britten: there is in fact a negative connection between these two, which speaks volumes. Boulez was never programmed at the Aldeburgh Festival during Britten’s lifetime, while Boulez never conducted any of Britten’s music.

- Boulez and Beethoven (also Berlioz): Boulez once remarked “the artists I admire – Beethoven, Wagner, Debussy, Berlioz – have not followed tradition but have been able to force tradition to follow them”.

Beethoven and Bach

Beethoven was born in 1770, twenty years after Bach’s death. He died in 1827, two years before the great moment of Bach revival: a performance in Berlin of Bach’s St Matthew Passionarranged by Felix Mendelssohn. Bach’s works were barely published or otherwise available in Beethoven’s lifetime, so we might reasonably expect him not to have come across the earlier composer’s work. However, letters from Beethoven to his publisher find him pleading to be send manuscript copies of Bach’s music. It is possible that a motif in his EroicaSymphony (no. 3) contains an allusion to B-A-C-H (or the notes of B-A-C-B flat). And touchingly he lobbied for financial assistance for Susanna Bach, the youngest of Bach’s children and the only one who survived into the 1800s. His descriptions of Bach were reverential, once declaring him “the Immortal God of harmony”. And he made punning use of the meaning of the word Bach (brook in English) writing in 1725 “his name should be not Brook but Ocean, because of the infinite and inexhaustible wealth of his tone combinations and harmonies”.

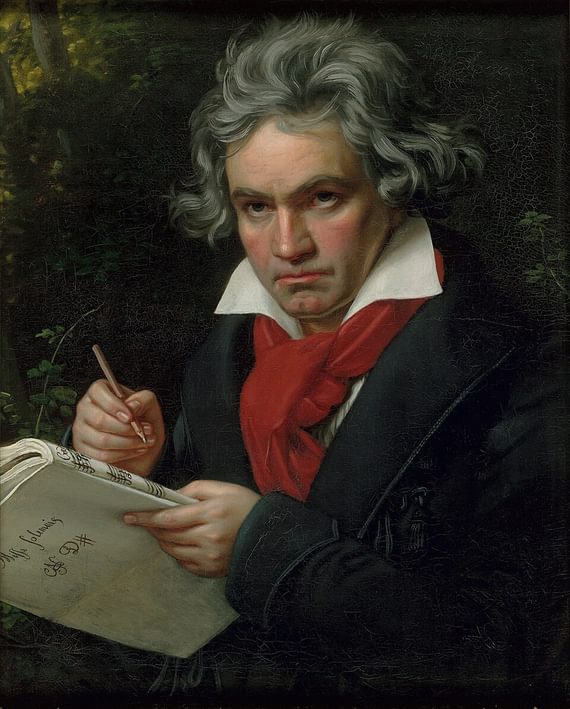

Beethoven

Beethoven at the Festival

14 June String Quartet no. 9

15 June Symphony no. 8

19 June String Quartet no. 3 and String Quartet no. 16

24 June String Quartet no. 14

25 June String Quartet no. 11

Bach at the Festival

18 June Markus Passion

21 June Brandenburg Concerto no. 5 and Orchestral Suite no. 2

27 June Cello Suite no. 3

- Beethoven and Brahms: both composers are buried in the same cemetery, the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna.

- Beethoven and Berlioz: Berlioz remarked after hearing Beethoven’s third and fifth symphonies “Beethoven opened before me a new world of music, as Shakespeare had revealed a new universe of poetry”.

- Beethoven and BAB: in 1976 the Big Apple Band (BAB) and Walter Murphy created a disco version of the first movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, called A Fifth of Beethoven.

Boulanger and Boulanger

Nadia and Lili Boulanger were two of the most accomplished and respected musicians of the twentieth century. The two sisters were also daughters of musicians: their mother, Raissa Myshetskaya, was a Russian princess who had married her much older singing teacher at the Paris Conservatoire, the composer Ernest Boulanger. Lili, the younger sister, began composing as a child, though due to ill health had to study privately rather than at a conservatoire. Her musical language was distinctive and experimental, as was her taste in drama. She left behind an unfinished opera at her death, La princesse maleine, an unusual fairytale of love thwarted by war. She died, aged only 24, in 1918. Nadia gave up composition after Lili died to concentrate on teaching, and became a hugely influential figure to such composers as Elliott Carter, Philip Glass, and at least two other ‘Bs’: Lennox Berkeley and Grażyna Bacewicz. She also found fame as a conductor, and was the first woman to lead the London Philharmonic Orchestra in 1936. She died in 1979, aged 92.

Lili Boulanger

Credit: Henri ManuelBoulangers at the Festival

24 June Mélodies and Lieder

- Nadia Boulanger and Bernstein: In a 1977 documentary Leonard Bernstein paid tribute to Nadia: “she is incredible. Indomitable! A grand lady of nearly 90 who is almost blind… She is radiating light”.

- Lili Boulanger and Berlioz: both these composers won the prestigious Prix de Rome prize for composition in 1913 and 1830 respectively. Lili Boulanger was the first woman to do so.

- …and Boulanger: Lili’s father Ernest won it in 1835, and Nadia Boulanger came second in 1908.

Main image: Benjamin Britten and Frank Bridge © Britten Pears Arts

Read next

Britten’s A.M.D.G.

As we look forward to the BBC Singers’ performance at the 76th Aldeburgh Festival, we dive deeper into the ‘hidden gem’ that is Britten’s…

Ensemble Renard

During a recent visit to Snape Maltings, James Gilbert and George Strivens from Ensemble Renard sat down for an interview with our very own…

Work of the Week 17. Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge

Presented by Christopher Hilton